Sainsbury’s game meat has high lead levels

Introduction:

Here we describe the results of analysis of samples of game meat purchased online or from Sainsbury’s stores.

The context to this study is that lead is a poison and has been removed from many previous uses (water pipes, paints, petrol, fishing weights) over time. And yet we continue to use lead ammunition in recreational shooting in vast quantities each year. Lead shot is overwhelmingly the commonest form of ammunition used for killing ‘small game’ such as Rabbits, Wood Pigeon, Pheasants and both species of partridge. Some of that lead-shot game is eaten privately by the shooter or enters the human food chain through game dealers, butchers and large supermarkets.

The Food Standards Agency warns against eating large quantities of game shot with lead ammunition and advises pregnant women and those trying to become pregnant to avoid eating such meat and that it should not be fed to young children. Ingesting lead can have a variety of physiological impacts on different parts of the body but the emphasis on children is because the central nervous system is susceptible to lead. Decreases in the IQ scores of children are associated with increases in blood lead level. Health authorities consider that there is no safe threshold level of exposure to lead, below which there is no risk of harm.

Surely government regulations protect us against eating meat with lead in it? The current situation is bizarre; Maximum Levels (MLs) for lead exist for most meats such as chicken, beef, pork etc, but not for game meat which is shot with ammunition, very often lead ammunition. The ML for lead in most meats is 0.1mg/kg wet weight (WW); that’s 1g of lead in 10,000,000g of meat, or 1g of lead in 10,000kg of meat – a standard portion of meat is around 80g (0.08kg).

Because there are no MLs set for lead content of game meat, most consumers (with no specialist knowledge of lead levels in foods) have to trust retailers to provide food for sale with low lead levels, or for retailers to flag the health impacts of high lead levels in such meat, or for the suppliers of shot game to switch away from lead ammunition to the many non-toxic alternatives. There is very slow progress on any of this.

Why did we pick on Sainsbury’s game meat to analyse? Sainsbury’s is a big company and it ought to be well aware of all of the above. Sainsbury’s is selling game meat with a prominent British Game Alliance logo on it and the packaging prominently states that it is ‘ideal for a healthy casserole or game pie’. At the back of the packet there is a small warning that mentions that shot might be in the meat, but not that the shot is probably lead and not that ingesting lead has health implications for all, but especially for young children. The front of the packet says ‘healthy’, the back of the packet does not even flag health concerns. And when Sainsbury’s were asked about lead in their game meat they clammed up very quickly, passed enquirers on to their supplier, Holme Farmed Venison, who have not answered enquiries about lead levels in the game meat that they supply.

That’s why we thought it worth testing Sainsbury’s game meat for lead levels – because they would not tell us or anyone else about the levels of a poison in their meat.

We expected to find high levels of lead in Sainsbury’s game meat because all similar studies of lead-shot game meat have found high levels of lead in them. We thought that it was unlikely that Sainsbury’s had ensured that they had removed the possibility of lead being in the meat they sell to their customers because we thought they would have said so. But you never know until you look, and so we looked.

Methods:

20 Sainsbury’s British Small Whole Chickens (to act as a control), 20 Holme Farmed Venison Diced Game Casserole Mix packs and 10 Holme Farmed Venison packs of Pheasant breasts were purchased in Sainsbury’s stores or from Sainsbury’s online between 8 January and 10 February 2021 (more details in Appendix 1 below).

Samples from each purchased pack were taken, labelled and frozen. From the chicken meat, two samples were taken from the breast and one from each leg, making a combined total weight of 20-40g per bird.

Frozen samples were sent to a laboratory for analysis where they were desiccated, ground down and then a sample of the milled dried meat analysed with standard techniques by a team with experience in this type of chemical analysis (for more details see Appendix 2).

Results:

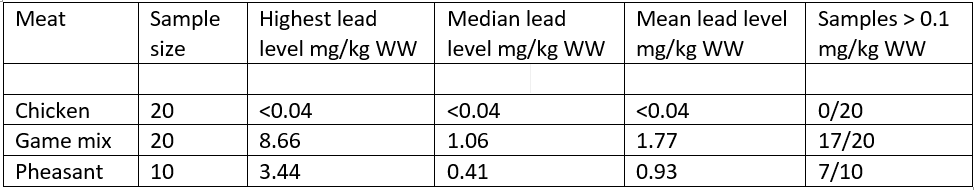

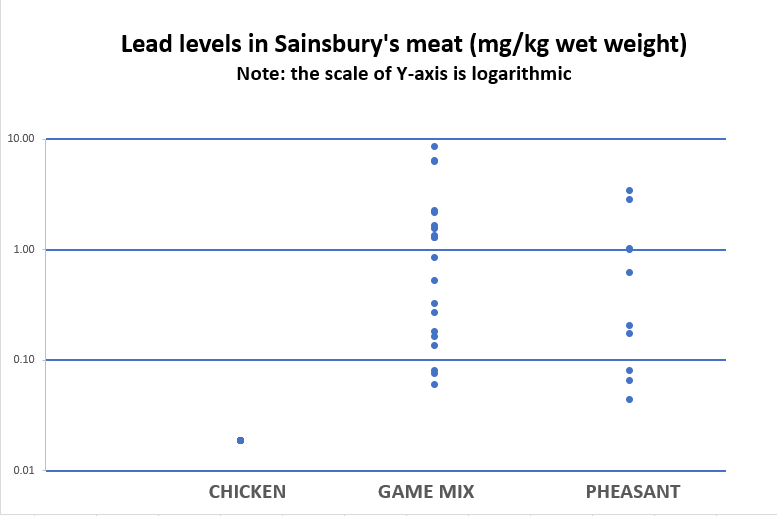

No lead shot was found in any of the samples, consistent with Sainsbury’s saying that lead shot are removed. However, what were the lead levels?

All 20 of the chicken samples had lead levels below the limits of detectability for the process – less than 0.04 mg/kg WW. They were all, therefore, well below the ML of 0.1 mg/kg WW which is set by regulation.

But it’s a different situation for game meat. Despite there being no lead shot found in these samples the lead levels are high – so high that if the ML for lead in meat did apply to game meat Sainsbury’s wouldn’t be able to sell this meat (24 out of 30 samples were above the ML).

The highest recorded level in this relatively small sample of game meat is at least 200 times higher than that present in the chicken samples, and 87 times higher than would be legal in chicken, pork, beef, etc.

Discussion:

These results are in line with previous studies. They don’t really show anything very new but they are of high relevance to public policy, retail practice and the public’s ability to make informed choices about what food to buy.

If government applied the same ML to game meat as is applied to other meats then lead-contaminated meat would essentially disappear from our tables.

If government and the Food Standards Agency regularly tested game meat for lead levels, and publicised the results, then we, and others, wouldn’t have to. Actually, a government body, the Veterinary Medicines Directorate, has been measuring levels of lead in venison, pheasant and partridge destined for consumers for many years, but they do not publicise their results.

If the Food Standards Agency made their health warnings about game meat prominent and if they required labelling of game meat with warnings then consumers would be making a more informed choice when buying such food.

If supermarkets voluntarily put warning labels prominently on their game meat then consumers could make a more informed choice and choose to eat high levels of lead if they wanted, and choose to feed high levels of lead to their children if they really wanted to do that.

If the shooting industry switched to the readily available non-toxic ammunition then this would be a done deal.

Sainsbury’s have not done a good job in protecting their customers from high lead levels in the meat that they sell, they have not done a good job in highlighting the health issues and they have not been open with customers who have asked them specifically about these matters. We’re not impressed by Sainsbury’s on this issue.

Waitrose is the supermarket which has reacted to this issue the best. We also collected 20 samples of Pheasant meat from Waitrose stores and got them analysed. We will report on those findings tomorrow.

Acknowledgements:

This study was entirely funded by supporters of Wild Justice donating money to our general funds – thank you! We’d like to thank Dr Mark Taggart and Dr Yuan Li of the Environmental Research Institute, University of the Highlands and Islands, Thurso, for carrying out the lead analysis. A variety of friends and colleagues helped with this project, collected samples, commented on drafts of this blog or helped in other ways.

Wild Justice:

Wild Justice is a not-for-profit organisation set up by Chris Packham, Ruth Tingay and Mark Avery. We are entirely dependent on donations. To support our work – click here. To hear more about our campaigns and legal cases subscribe to our free newsletter – click here.

Appendix 1

The meat samples were bought at the following Sainsbury’s supermarkets: Chicken; Romford, Ilford, South Woodford, Walthamstow, Stratford City and Beckton (all London), Brentwood (Essex) and Biggleswade (Beds); Game Mix; Romford, South Woodford and Beckton (all London), Brentwood (Essex), Hoddesden (Herts) and Biggleswade (Beds); Pheasant breast; online (4), Beckton (London), Brentwood (Essex) and Hoddesden (Herts).

Appendix 2

The frozen samples were first dried in a drying oven at 65°C to constant dry weight. The average wet weight sample size was 38.3g, dropping to 11.8g after drying – giving an average moisture content of 69%. Dried samples were then milled to a fine powder and stored in zip-lock bags in a desiccator post mill to ensure they remained dry. Milling was undertaken very carefully to ensure thorough cleaning of the mill between samples, using dry lab tissue and a stream of compressed air to remove all residual particles of material. Milled samples were digested using a microwave digestion system and pressurised Teflon vessels – using trace metal grade nitric acid and trace metal grade hydrogen peroxide. A 0.4g subsample of each powdered sample was digested and following complete dissolution solutions were made up to 15ml volume with Type I Milli-Q ultrapure water. In parallel with samples, blanks were run to attain a procedural limit of detection for the process, and a certified reference material (CRM) was used to ensure Pb recovery was within tolerance (strawberry leaf powder (LGC 7162) was used as the CRM, with a certified Pb level of 1.8 +/-0.4 mg/kg DW). Once digestions were complete, all samples/CRMs/blanks were analysed using an ICP-OES system (Agilent 5900). The instrument was calibrated against five Pb wavelengths and the 220.353nm Pb line was used for final data processing/calculations. CRM recovery was within the above CRM tolerance. Analysis was undertaken at the Environmental Research Institute, University of the Highlands and Islands, Thurso, Scotland.