Low convictions allowing wildlife crime to go unpunished, say nature groups

Wildlife & Countryside LINK’s Wildlife Crime Group (of which Wild Justice is a member) has published its latest report on wildlife crime that took place across England and Wales in 2022.

Here is the WCL press release:

Low convictions allowing wildlife crime to go unpunished, say nature groups

Some of the country’s leading nature voices are today releasing analysis showing that our cherished wildlife is being failed in the courts, with people who commit crimes (including persecution of birds of prey, badgers and bats) rarely being convicted. Such a lack of convictions removes a key deterrent for would-be criminals and makes it more likely for people to become repeat offenders. Wildlife crime can also be linked to other serious crimes like firearms offences and organised crime.

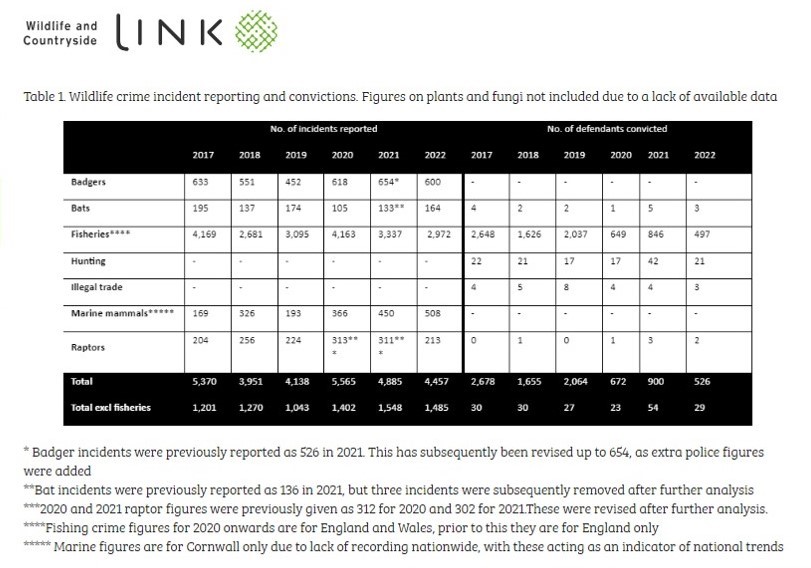

The Wildlife Crime Report for 2022, compiled by Wildlife and Countryside Link, with information from groups including RSPB, WWF UK, and the League Against Cruel Sports, has shown that convictions for crime against wildlife in 2022 decreased substantially. This is despite a record number of reports of wildlife crime over 2021. Other wildlife crimes include the disturbance of seals and dolphins, and the illegal trade of wildlife across international boundaries.

In 2022, Link estimates that there were around 4,457 reported wildlife crime incidents in England and Wales, compared to 4,885 in 2021 (a record level sustained from a surge in incidents in 2020 during the pandemic). Despite record levels of wildlife crime in 2021, there was a notable 42% fall in subsequent convictions for wildlife crime, from 900 in 2021 to 526 in 2022.

Dominic Dyer, Wildlife and Countryside Link’s Wildlife Crime Chair, said: “To put it simply, people who hurt wildlife are getting away with it, with a lack of convictions leaving them free to cause further suffering. Despite shockingly high levels of wildlife crime in recent years we’re not seeing higher levels of convictions to give nature the justice it deserves.

“With the Government’s deadline to halt the decline of nature by 2030 getting ever closer, it’s time for ministers to take the issue of wildlife crime seriously. This means the Home Office making it a notifiable offence to help police forces identify crime hotspots and plan accordingly.”

Despite a slight fall in the overall number of reports of wildlife crime, the report shows that reports of disturbances on marine mammals (including seals and dolphins) rose from 450 in 2021 to 508 in 2022. This is likely due to the rise in the number of people participating in outdoor activities on or near the coast including walking, paddle boarding, kayaking and jet skiing, as well as wildlife tours and wild swimming. Marine experts and water sports governing bodies are working to educate the public on how to enjoy our beaches and ocean without putting the welfare of marine wildlife at risk.

Sue Sayer MBE of Seal Research Trust, said: “More people enjoying our ocean is great news for health and wellbeing, but we must be more mindful of how this can impact marine wildlife including seals. If a seal gets scared by people getting too close it will use huge amounts of energy to scamper away and could also risk serious injury when getting back into the water. Fortunately, it’s very easy to enjoy our beaches and ocean without putting seals at risk of harm. Just follow the Defra Marine and Coastal Wildlife Code, Give Seals Space (100m+), and slowly move further away from seals if they start to look at you.”

Bat crime figures for 2022 increased by 23% compared to 2021. A survey issued by the National Wildlife Crime Unit to the 43 police forces across England and Wales (19 responded meaning these numbers are likely far less than the true extent of crime), coupled with reports to Bat Conservation Trust revealed 164 cases of bat crime. The most common form of bat crime is disturbance or destruction of roosts, often due to property development. The report points to a case in Monmouthshire of a developer being fined more than £7,000 after renovating an old school building where bats were known to be present.

Kit Stoner, chief executive of Bat Conservation Trust, said: “Bats are long lived, roost faithful, and slow to recover from population losses. Unfortunately, many species of bat in the UK are under threat from loss of roosting sites. With the most common form of bat crime being disturbance or destruction of roosts, it is vital that we maintain and enforce protections. Without this action, we will not meet targets to halt the decline of species.”

Due to a lack of official data, these figures on crime (most of the data relies on direct reports from members of the public to nature groups) are likely to be a significant under-estimate of wildlife offences. Wildlife and Countryside Link is therefore calling on the Home Office to make wildlife crime notifiable, to help target resources and action to deal with hotspots of criminality.

To properly tackle the issue of wildlife crime, nature experts are calling for the following actions (most of which were also recommended by a UN report in 2021):

- Making wildlife crimes notifiable to the Home Office, so such crimes are officially recorded in national statistics. This would better enable police forces to gauge the true extent of wildlife crime and to plan strategically to address it.

- Increasing resources & training for wildlife crime teams in police forces. Significant investment in expanding wildlife and rural crime teams across police forces in England & Wales, would enable further investigations, and lead to further successful prosecutions. Funding for the National Wildlife Crime Unit should be increased in line with inflation, to allow the Unit to continue its excellent work.

- Reforming wildlife crime legislation. Wildlife crime legislation in the UK is antiquated and disparate. A 2015 Law Commission report concluded these laws are ‘‘overly complicated, frequently contradictory and unduly prescriptive’’. Much of this stems from the need to prove ‘intention and recklessness’, which has stunted the potential for prosecution in even clear cases of harm being done to protected and endangered species.

ENDS

The report can be read/downloaded here.